The desert war has always had an allure—a kind of cinematic clarity. No mud. No trench rot. Just heat, steel, sand, and the clash of wills on a vast stage. And at the centre of it all, storming across the horizon in his open-top command vehicle, was Erwin Rommel.

Rommel in Africa is more than just a recounting of battles—it’s a study in style, audacity, and the razor-thin margins between brilliance and disaster. This document, likely compiled for internal analysis or postwar military education, lays out the defining campaign of Rommel’s career with stark, clinical precision. But behind the maps and movements, a story of strategy, improvisation, and sheer force of character emerges.

When Rommel arrived in Libya in early 1941, he wasn’t supposed to launch a major offensive. His orders were to hold the line and prevent total Axis collapse after Italy’s humiliation by the British. But that was never Rommel’s way. Within weeks, he turned the tables, hurtling east across Cyrenaica, outpacing supply lines and bewildering British commanders. Benghazi fell. Then Mechili. Then, astonishingly, he besieged Tobruk.

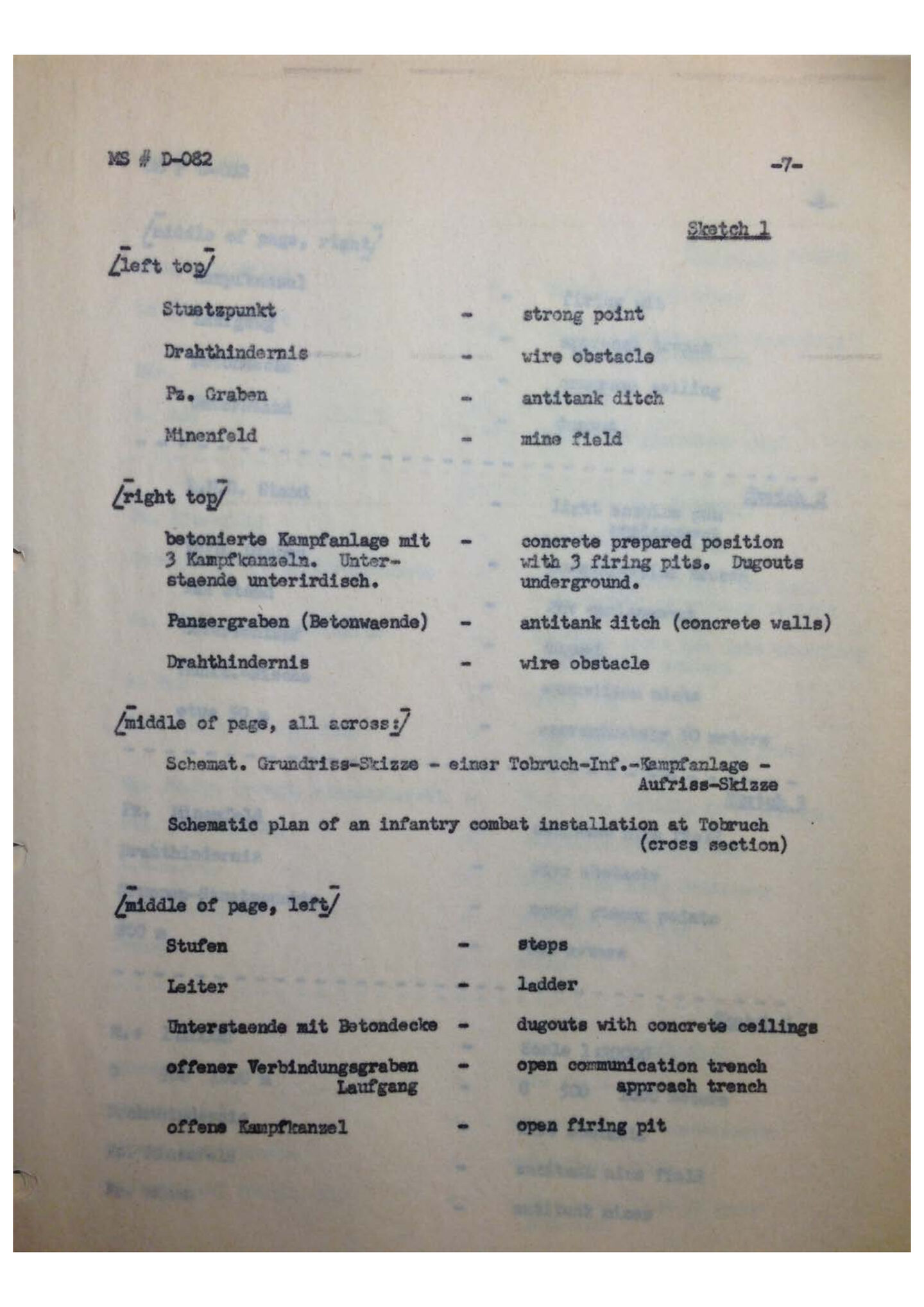

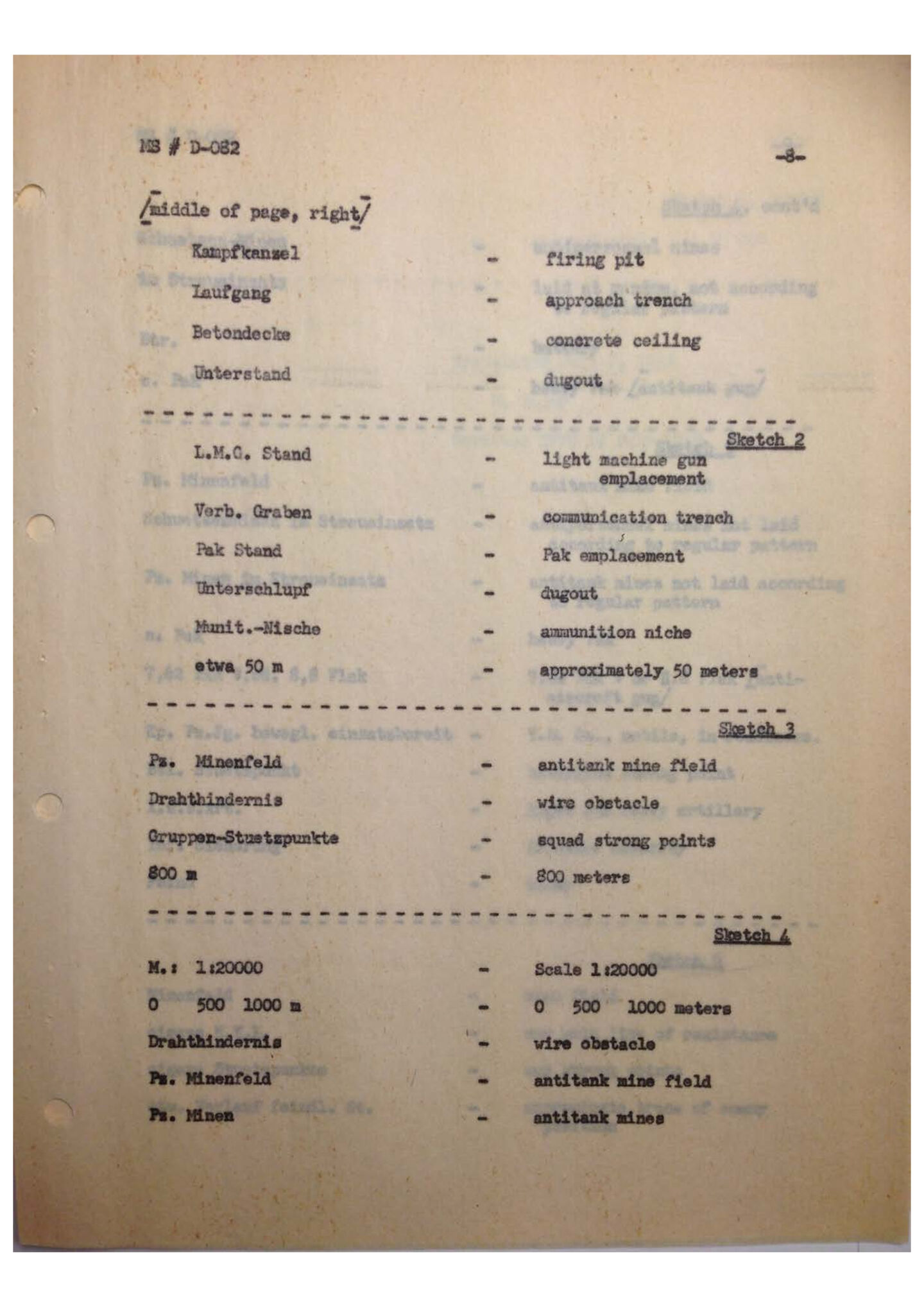

This document captures that early momentum beautifully. It shows a commander who understood tempo—who seized initiative before the enemy could think. He used terrain like a master, masking his movements with sandstorms and deceptive radio traffic. His reliance on speed and shock action—hallmarks of what we’d now call “mission command”—forced the British Eighth Army onto the back foot again and again.

But as the pages turn, so too does the tide of war. The study reveals the creeping fragility beneath the surface of Rommel’s campaign. For all his battlefield brilliance, logistics were his Achilles’ heel. The further he pushed, the more he strained supply. Fuel, ammunition, water—every mile east brought new challenges.

And then there was El Alamein.

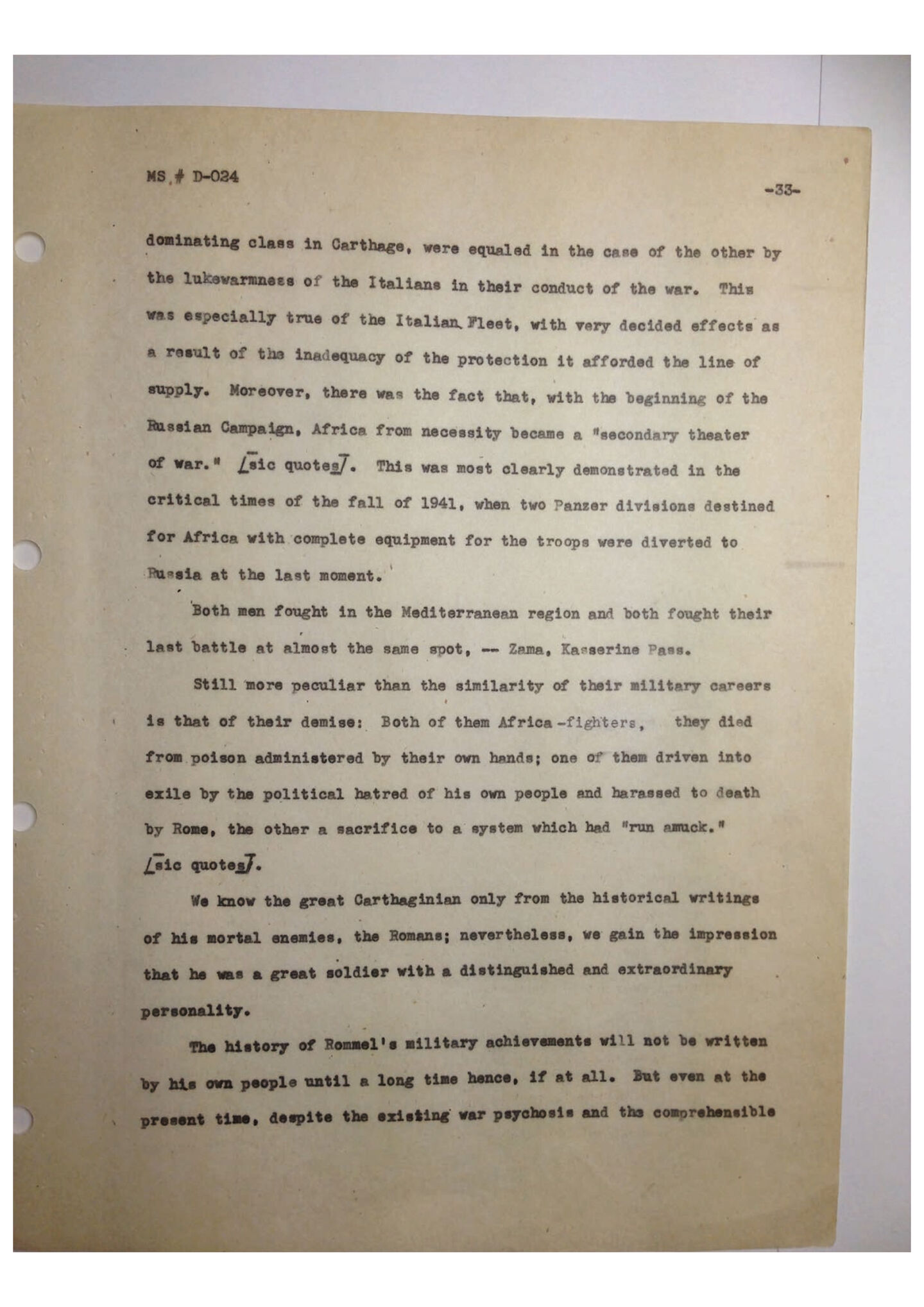

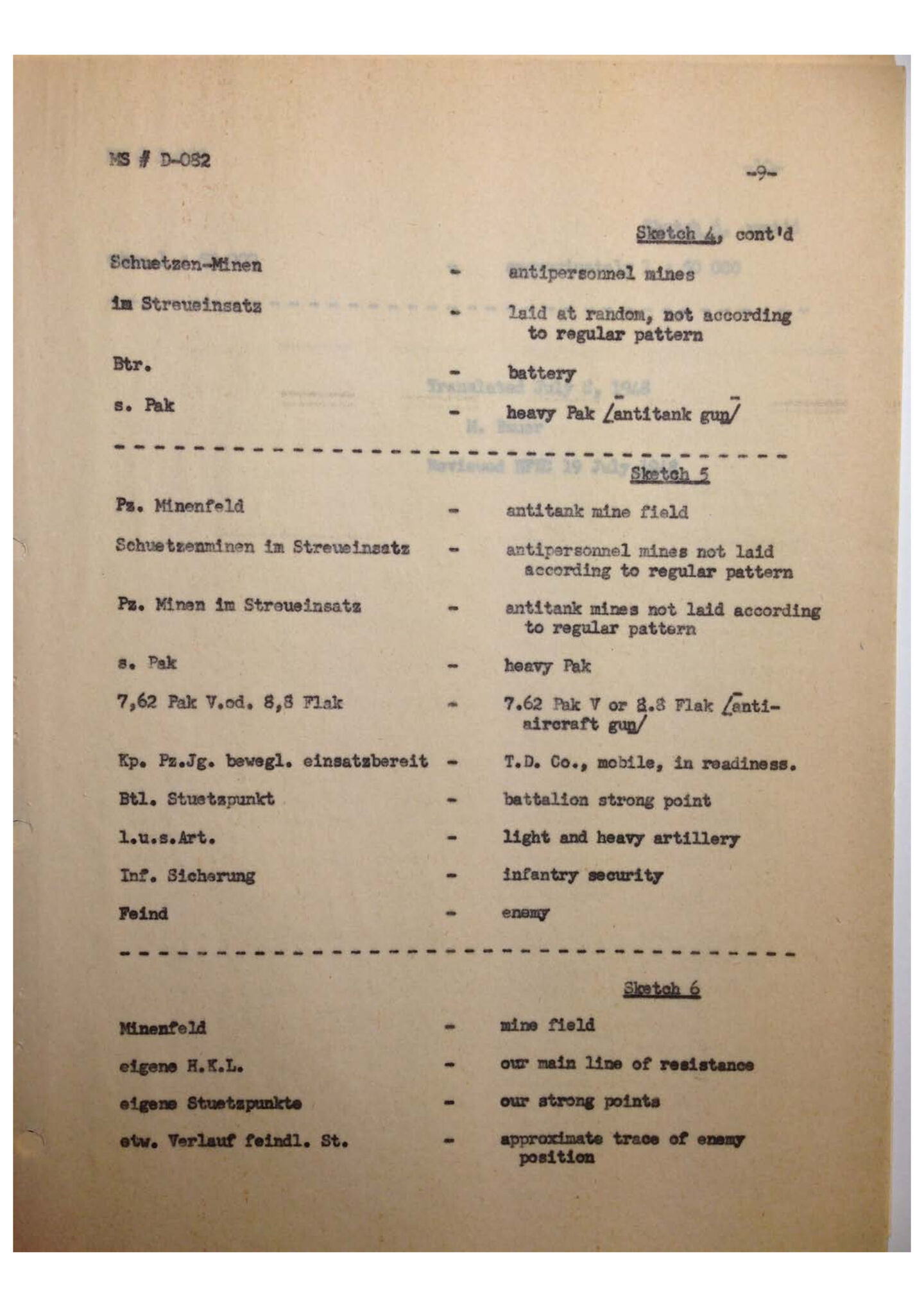

This report doesn’t shy away from it. Here, Rommel faced an enemy who had learned his methods. Montgomery, with time and overwhelming material superiority, anchored himself at a point Rommel couldn’t bypass. The Afrika Korps, outnumbered and exhausted, was ground down in set-piece battle. It was a brutal end to a brilliant phase.

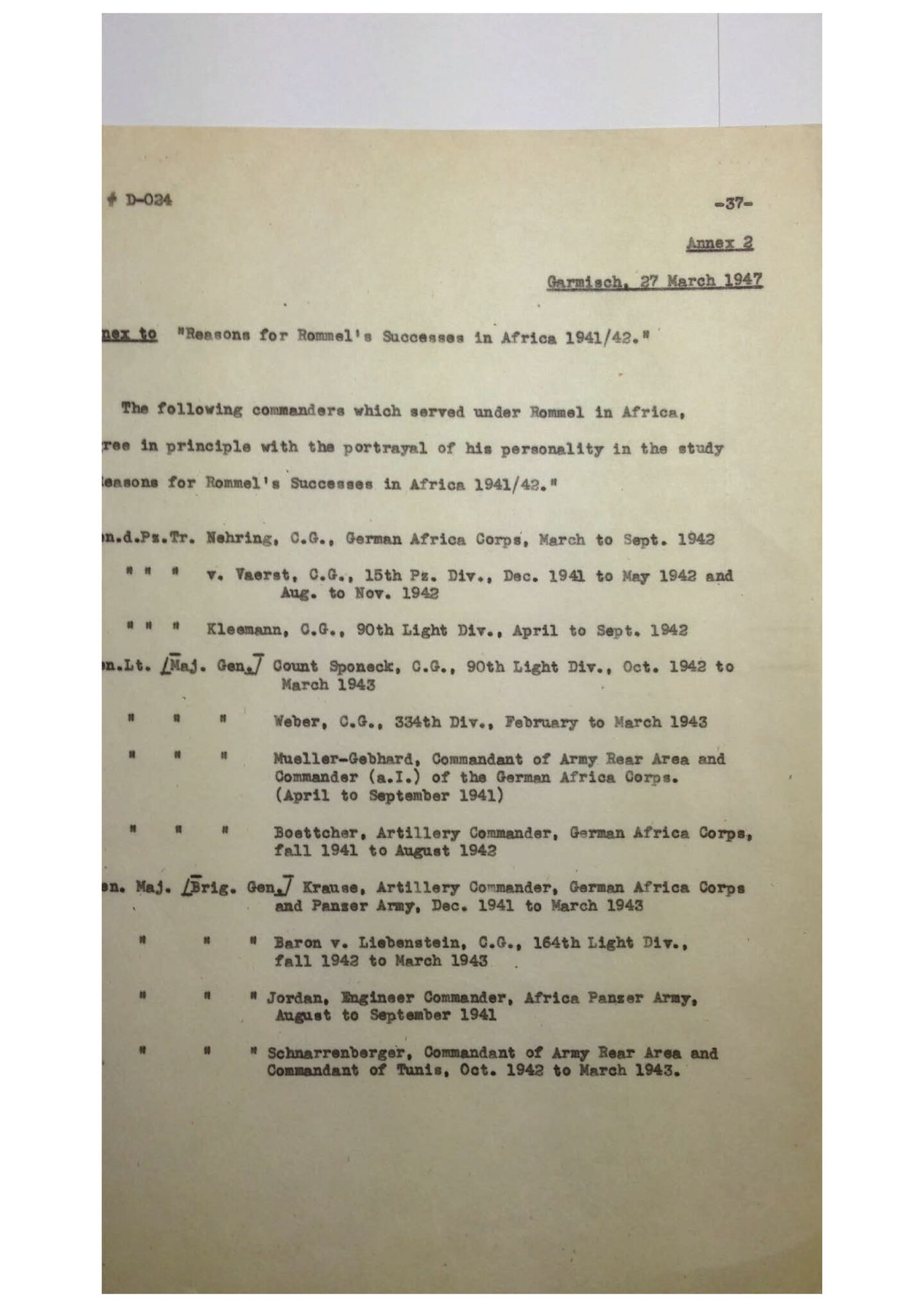

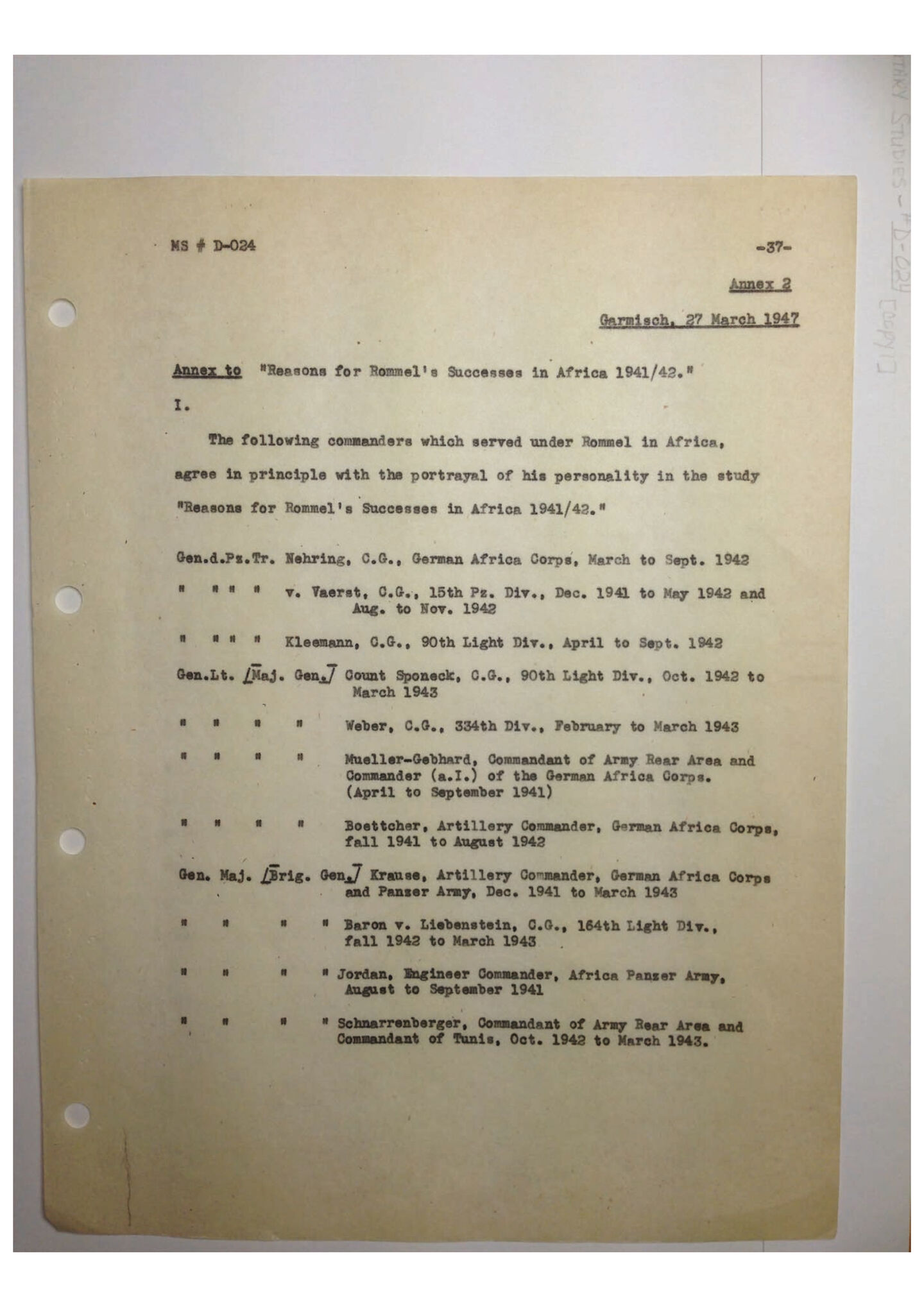

Yet what lingers from this account isn’t defeat. It’s the way Rommel adapted, endured, and inspired. The men who served under him respected him to the core. He wasn’t a distant strategist—he was out front, binoculars in hand, making decisions in the dust. He led from the front because he believed war was personal, not abstract.

This document hints too at his growing disillusionment. Rommel wasn’t a Nazi ideologue. He was a soldier—professional, pragmatic, and increasingly aware that Germany’s war was turning into something darker and unwinnable. His time in North Africa gave him clarity. He saw the value of fighting honourably, of treating prisoners humanely, of understanding that victory without ethics was no victory at all.

In the end, Rommel in Africa is as much a character study as it is a campaign analysis. It reminds us that Rommel’s legend wasn’t built just on tactics, but on temperament. He took risks others wouldn’t. He inspired men who had no reason to keep fighting. And though he lost in the end, he did so with a kind of tragic grandeur that makes his story endure.

For historians, officers, and anyone drawn to the drama of the desert war, this is essential reading. It’s not about myth—it’s about mastery.